Weekly Outlook

ECB behind the curve

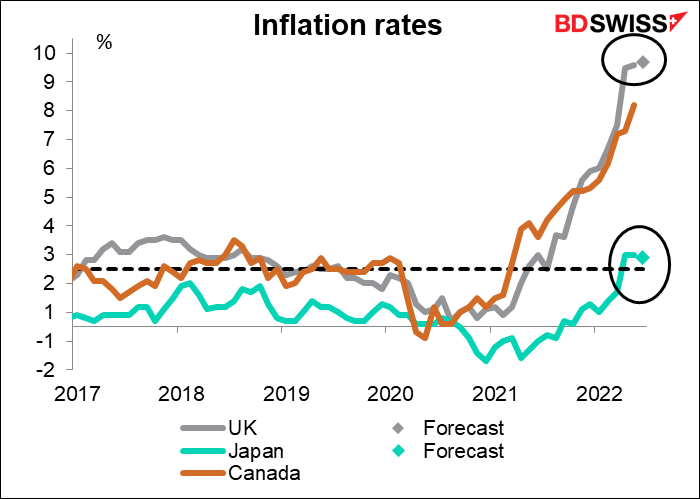

Investors are laser-focused on two things: inflation and central banks’ reaction to it. After this week’s shocking US inflation print for June – at 9.1%, higher than any economist had expected – the market brought forward its expectations for fed tightening. A few moments later the Bank of Canada ratified these expectations by hiking 100 bps, more than (almost) anyone had expected. The question now is, which central banks will follow along and at what pace? Because that’s what will largely determine how currencies move.

Following the surprise US CPI announcement, the market shifted from expecting a 75 bps hike at the July 27th meeting of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to expecting 100 bps (blue bars), followed by a 75 bps hike in September. Expectations for a 100 bps hike in July cooled on Thursday (red bars) after two voting members of the Committee came out in favor of 75, but investors are still braced for higher rates from the Fed.

There is one odd point to all of this: while inflation is surging around the world and mesmerizing investors, inflation expectations are actually falling even as actual inflation is rising almost everywhere. As the graph shows, the expected inflation rate over the next five years is now lower in the US and UK than it was at the beginning of the year!

The breakeven inflation rate is the inflation rate that gives the same return from buying a normal government bond and an inflation-linked bond of the same maturity (i.e., the inflation rate at which one would break even buying one bond and selling the other). It’s taken as the market’s forecast for inflation, since if people expected inflation to be different than that they’d buy one or the other until the expected return is the same.

How can this be? I’d say it’s a vote of confidence in central banks. People now believe them when they say, as the Bank of Canada did this past week, that they are “resolute in (their) commitment to price stability and will continue to take action as required to achieve the 2% inflation target.”

We can see this phenomenon particularly in the US, where the market’s forecast for inflation over the next year has come down in just the last month from 5.3% to 3.4%.

What does this say about the central banks that meet next week: the Bank of Japan (BoJ) and the European Central Bank (ECB) on Thursday? If we look at the breakeven inflation rates for Japan and the Eurozone (Germany, to be specific), we immediately see two things: 1) inflation in Japan is low and is expected to fall back below the BoJ’s 2% target, and 2) the ECB is literally “behind the curve,” in this case the curve being the expected US inflation rate.

This is of course because the ECB has so far refrained from hiking rates at all and instead just let inflation do its thing. You can see what an anomaly this is, globally. This table shows how the G10 countries plus the other countries in the G20 have changed their policy rates since they hit bottom in 2020/22. Only four — Indonesia, China, Japan, and the Eurozone – have held rates steady.

The mystery of Eurozone monetary policy becomes even deeper when you compare that data with where inflation currently is in those countries. (This chart excludes Brazil, Russia, and Turkey as extreme cases.) German inflation is almost double that of Indonesia, the next-highest country not to have moved its rates at all. It’s slightly higher than Canada, which has already hiked by 225 bps.

The problem is that the ECB has pre-committed itself to a policy that is no longer in step with the rest of the world. At its June meeting, ECB President Lagarde said, “we intend to raise the key ECB interest rates by 25 basis points at our July monetary policy meeting.” She reaffirmed that decision at the ECB’s Sintra symposium. There’s no meeting in August, but they’ll raise rates again in September, she promised, and that hike could be bigger. “If the medium-term inflation outlook persists or deteriorates, a larger increment will be appropriate at our September meeting.”

It’s of course possible that the Governing Council might change its mind about July. Lagarde was not under oath when she made that statement. Heaven knows, there are plenty of examples of central banks changing their minds without prior notice – the Swiss National Bank removed the EUR/CHF floor in 2015 just days after saying that the floor was one of the “pillars” of its monetary policy, thereby precipitating what I would guess was the sharpest move ever seen in the foreign exchange market.

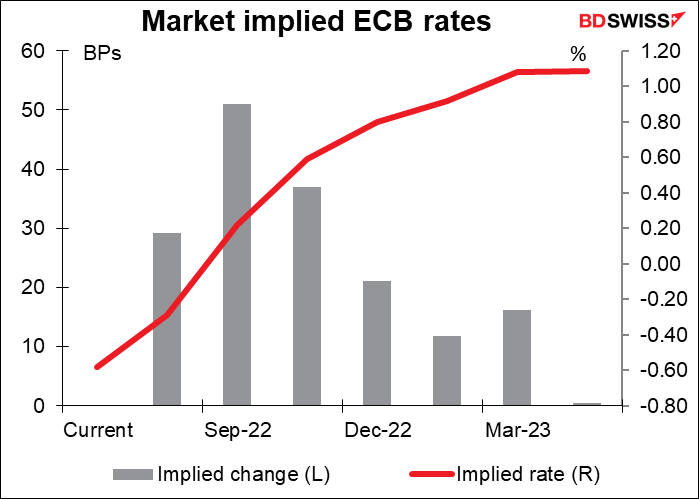

That’s not what the market expects, however. The market is discounting a 29 bps hike – a 25 bps hike as promised and only a small chance of anything larger. The Governing Council unanimously approved the 25 bps hike – it would be odd for them to overturn a unanimous decision. The excitement is penciled in for September, when the market looks for a 50 bps hike. That’s not much in the context of what other central banks are doing: the Bank of Canada hiked by 100 bps this week and the US is assumed to be moving in that direction, too, as mentioned above.

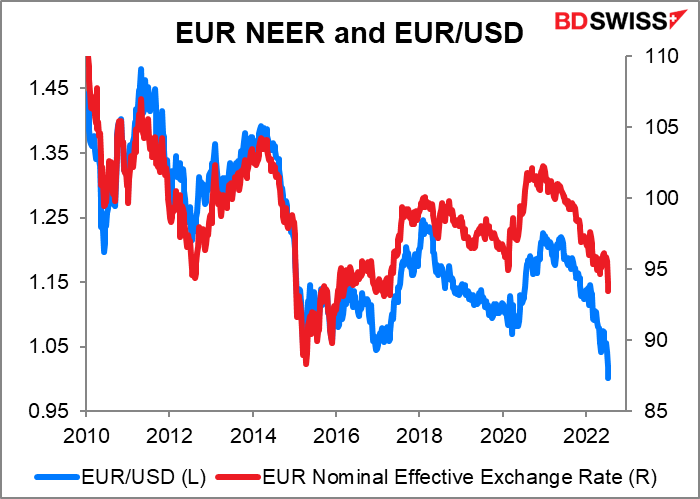

So not only is the ECB behind the curve, it’s expected to stay behind the curve, too. Its forecast pace of tightening is well below those of other central banks except the BoJ, which might as well be hibernating. It’s this “monetary policy divergence” that is the key to the euro’s weakness nowadays – and why the only major currency that’s weaker than the euro is the yen, which has the same background (except that inflation isn’t out of control in Japan yet).

What else might the ECB do at its meeting? The first point of interest will be what size the rate hikes in September and beyond might be. So far 50 bps looks likely. The Governing Council is likely to keep its pledge for a “gradual but sustained path” of tightening beyond September, “gradual” being a code word for 25 bps. The risk that Russia might cut off the supply of gas to Europe, thereby precipitating a recession, skews the risk to the pace of hiking to the downside for the later meetings.

And of course everyone will be waiting to hear what if anything Mdme Lagarde has to say about EUR/USD breaking parity. I expect that she won’t be particularly fussed. Much of the reason is dollar strength, not euro weakness. While this may be a 20-year low for EUR/USD, it’s not even a 10-year low for the trade-weighted index.

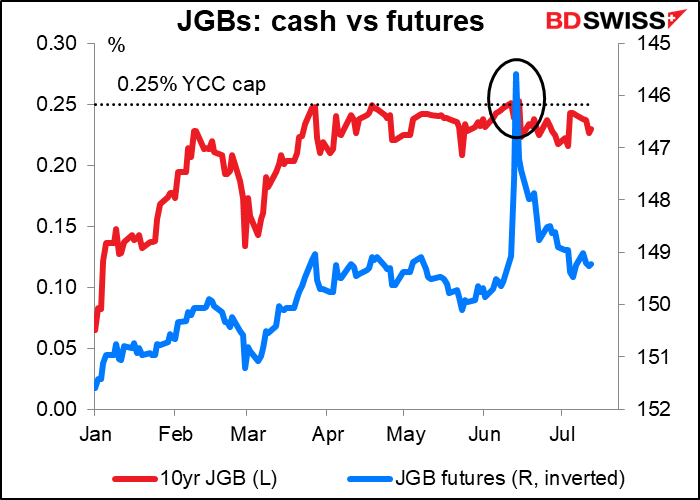

As for the Bank of Japan…I don’t see anything of note happening at this meeting. There was considerable speculation in the bond market ahead of the June meeting that the BoJ would dismantle its yield curve control (YCC) program, which capped the yield of the 10-year Japanese Government Bond (JGB) at 0.25%. The policy’s growing side effects (e.g. the distortion of the yield curve and the collapse of the yen), the fact that the Reserve Bank of Australia ended its YCC program, and the difficulty of communicating just how they would exit the program made investors – particularly foreign hedge funds – think that the time was ripe for a change.

The speculation sent the price of the futures plunging (interest rate soaring) as investors sold futures in expectation that they could later buy bonds cheaply to deliver against the futures.

That didn’t work out well for a lot of people, but at enormous cost to the BoJ – they spent an estimated $81bn hoovering up bonds to force speculators to close out their positions. That caused a near-record amount of fails in the JGB market (= traders who were obliged to deliver a bond but weren’t able to do so).

Now…quiet. Some days there aren’t even any trades in the second-biggest government bond market in the world. (Note: I started my career as a Japanese government bond analyst. Boy am I glad I got out of that business!)

I assume that this BoJ meeting will go pretty much like the others, with only some tinkering around the edges with minor aspects of their policy. They’ll probably allow the special pandemic fund-supplying operation to end as scheduled in September. I don’t expect any change to their forward guidance or the YCC program.

The meeting will include an updated version of their quarterly Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices. The Bank is likely to downgrade its growth forecast for FY2022 in line with the slowdown in overseas economies and raise its inflation forecast because of higher fuel and food prices. This is in line with what the market has been thinking anyway and so shouldn’t surprise anyone. The main point of interest will be what the BoJ thinks of the rise in long-term inflation expectations, which could be a driver for higher wages and thereby create the wage-price spiral that the BoJ and government have been hoping for for decades.

Other indicators next week: UK, Canada, & Japan inflation, more UK data, preliminary PMIs

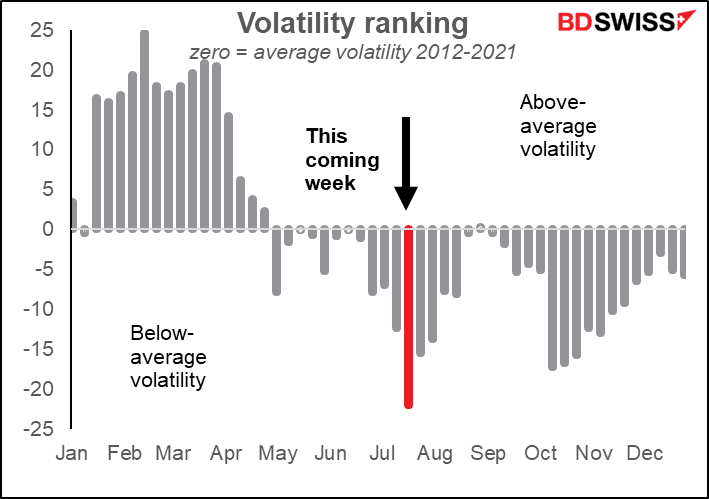

This coming week is usually the least volatile week of the year, but somehow I suspect that this year will be an outlier.

Currency volatility for each week is ranked from most volatile (100) to least volatile (0) of the year. We then take the average for 2012-2021. If volatility were distributed randomly, over time each week should have an average ranking around 50. The graph shows the divergence from 50. Weeks with positive bars have been more volatile than average, those with negative bars are less volatile

We’ll be getting inflation data next week from the UK and Canada (Wed) and Japan (Fri), as well as the final EU-wide CPI (Tue).

The UK CPI is expected to accelerate slightly, but that’s no surprise. At their meeting in June, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee said that “CPI inflation is expected to be over 9% during the next few months and to rise to slightly above 11% in October.” So a 10 bps rise as is forecast would just be in line with expectations and have no policy implications.

In Japan, the national CPI is expected to slow by 10 bps, which would only confirm in the minds of the Policy Board members that the rise in inflation over their 2% target is possibly just temporary and would justify their keeping policy on hold. JPY-

No forecast available yet for Canada’s CPI.

Other than that it’s a big week for UK data, with UK employment on Tuesday and retail sales on Friday in addition to the CPI. Bank of England Gov. Bailey will speak Tuesday at the annual Mansion House Financial and Professional Services Dinner.

And of course everyone will be watching the contest for UK Prime Minister, which looks like it’s going to come down to a race between former Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak and Minister for Trade Policy Penny Mordaunt. The big problem that all candidates face is that they can’t win the nomination without the support of the hard-core Brexit faction, but what the hardcore Brexit faction wants is impossible to achieve. EG the Northern Ireland border problem has no solution. The problem of illegal immigrants has no solution. Tax cuts are wonderful but how to cut taxes and narrow the budget deficit without cutting spending? Etc etc. We will hear lots of promises but they will all be just sound and fury, signifying nothing.

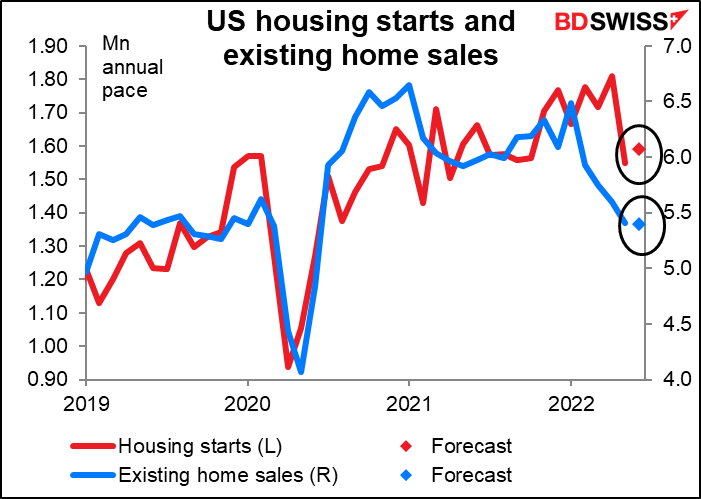

There’s not that much coming out from the US during the week. FOMC members will be in “purdah,” the two-week blackout period ahead of the FOMC meeting when they’re not allowed to talk about policy in public. The only indicators of note are housing starts (Tue) and existing home sales (Wed). Housing starts have plunged recently; they’re expected to pick up a bit. But sales are expected to fall slightly as rising mortgage rates work their magic on the US economy.

On Friday we get the preliminary purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for the major industrial economies. They’re expected to be down across the board, with all of the PMIs creeping toward the 50 line that separates expansion from contraction. This is likely to further the narrative that recession is approaching, which could be negative for the commodity currencies. It could be positive for JPY however if it implies central banks elsewhere won’t have to raise interest rates as much.

Other indicators worth watching include the German producer price index (Wed); trade data from New Zealand and Japan (Thu); Canadian retail sales (Fri); and a speech by Reserve Bank of Australia Gov. Lowe (Wed).

Other things to watch: Italian PM Mario Draghi will make a speech to the Italian Parliament on Wednesday. He offered his resignation after his coalition partners, the Five Star Movement, failed to back him in a confidence vote in the Senate, but President Mattarella rejected the resignation. It’s unclear what will happen next. Early elections remain a possibility if they can’t reach an agreement. Political instability in the Eurozone’s third-largest economy is not good for the euro, although it may be that the markets are used to it by this time. (I remember one time in the 1980s when the Italian lira rose after the government fell because traders thought the country would run better with no government!)